Public education is a public good

Who benefits from public education?

Certainly, the individual student does. It provides them with skills to take part in society and the economy. It gives them access to culture and traditions, as well as exposure beyond a narrow personal experience.

But public education has broader social purposes and contributions as well. It is the basis for social benefits that are of value to the collective, as well as the individual. It provides experiences and the skills to be a participant in a democratic society, essential for the collective, as well as the individual interests. If the conditions are right, it should provide the basis for a more equitable society characterized by universal rights and access where efforts are put into producing equality of outcomes. It builds community, both in physical spaces and social connections.

Privatization in education, in contrast, is focused significantly on individual rather than collective interests. Rather than the public good, its central motive may be financial profit, advantage for a particular group, or even isolation from the diversity of the mix that is public education.

Privatization has many faces. To protect public education as a public good it is necessary to identify these, to analyze how they impact public education and to suggest responses that serve to support the public over the private good.

Some forms of privatization are quite obvious. Public funding of private schools. Public schools contracting out of educational services. Recruiting international students primarily for their tuition. Others are less apparent or visible, such as perks for decision-makers from education technology companies, or creating programs that are only available to students who can pay fees.

Adopting business models for decision-making about educational programs is another form of privatization, as Brownlee, Hurl and Walby (2018) identify how.

Public institutions increasingly use market-like mechanisms to deliver services and are being run according to market oriented principles, such as competition, cost-reflexive pricing, financialized performance indicators, and competitive outsourcing. Corporatizing Canada, p. 5

This report identifies some of the privatization practices evident in British Columbia schools, and proposes some responses to promote the public, rather than private, good.

Market-like mechanisms as privatization in BC

The BC Liberal government in 2002 introduced a number of policies aimed at introducing market-like mechanisms into BC's public school system. These were lauded as expanding "choice" in the system and included

- declaring open boundaries between and within school districts,

- creating Distributed Learning (DL) programs as competition among school districts and with independent (private) school DL programs,

- encouraging entrepreneurial activities like recruiting international students and opening overseas BC schools,

- encouraging the growth of independent schools and

- reporting the scores from FSA tests on a school-by-school basis that allowed for school rankings by the Fraser Institute.

The growth of the use of digital technology over the past fifteen years has also brought into the public school increasing elements of corporate influence in the form of ubiquitous tools.

Two external factors helped to propel the adoption of this market competition model. School districts were looking for funds because of austerity budgets that meant they have fewer resources than required to meet educational demand. Austerity was a global trend, promoted by neo-liberal ideas that the role of government should be reduced. The BC Liberal government elected in 2001 adopted these policies, starting with a 25% tax cut as a first act. Reduced government tax revenues created a deficit that was met by reduced budgets for public services. Dealing with the problem was then downloaded to school districts.

Further, student enrolment was in decline, which created further financial shortfalls because cost reductions couldn't be as easily made as reductions in funding. School districts sought ways of dealing with their funding shortfalls through the market mechanisms government opened to them.

Both of these situations have changed in 2019. The current provincial budget shows a surplus, even after the costs of restoring the provisions of the BCTF collective agreement by the Supreme Court of Canada and covering some of the deficits created by the previous government in BC Hydro and ICBC. Also, student enrolments are now increasing overall in the majority of school districts, particularly in the urban areas.

How has the market-like approach played out in specific areas of BC education? How has it affected the public good of equity, in particular? What are the opportunities to changing policies and improving equity by abandoning these market-like practices?

1. Distributed Learning (DL) has been increasingly privatized

The Distributed Learning system was explicitly designed to be a competitive model. Individual students in Grades 10 to 12 were told by provincial policy that they could take any of their courses through registering for a Distributed Learning course in any school district. The policy indicates they can make this choice without requiring the approval of either their parent or the school counsellor, or other school official. This "choice" system also allows students in public schools to choose to take courses at an independent school DL program, and the course results are indicated on their public school transcript.

When this policy was adopted in 2002, only a minority of school districts had Distributed Learning programs. However, soon nearly every district got into the business. They were driven to compete for students because with per-course secondary funding, each registration brought funding into the district. Aggressively competitive districts could supplement their funding by attracting students from other districts. Even reluctant districts created programs because of fear that some of their students would take courses in other districts and lead to a loss in funding.

The dash for funding was exacerbated by the fact, as experienced by most DL teachers, that the district expenditures on DL were less than the funding brought in, providing a subsidy for other school district program areas.

In the current context, many districts have moved away from seeking DL students from outside their own district and enrolment in public school DL programs has declined overall. The combination of growing enrolments and more funding because of the restoration of the collective agreement, have created a less competitive environment. In addition, many districts have moved to blended learning or hybrid programs, seeking to link DL to situations where students have personal contact with a teacher, rather than entirely online, with positive results for the quality of the educational experience.

The market model has led to significant growth of independent school DL programs. This is a result of the competitive model, along with aggressive promotion by private schools (particularly Heritage Christian's "BC Online School"). Ministry finance policies have also given an incentive to enrolment in the independent schools because they are allowed to provide a subsidy to parents for internet access, but public school DL programs are not.

More students are publicly funded in the private DL schools than in the public DL schools. About one quarter of the overall enrolment growth in publicly-funded independent school enrolment since 2002 has been in the DL schools. This includes the public school students taking individual courses in the independent DL programs.

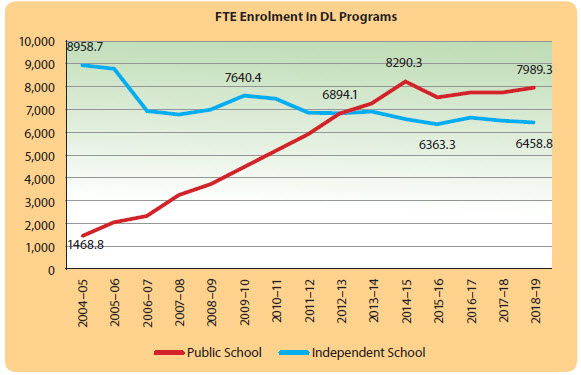

Over the 15 years from 2004-05 to 2018-19, the number of students in independent schools DL programs increased by close to four and a half times, while the number dropped by 2,500 in the public schools.1

Source: BC Ministry of Education. (2019). BC Schools - Student Enrolment and FTE by Grade

This will change only if government alters funding policies or enrolment policies to support keeping students taking DL courses in public DL programs in the districts where they are attending public schools.

2. International student revenue increases inequality

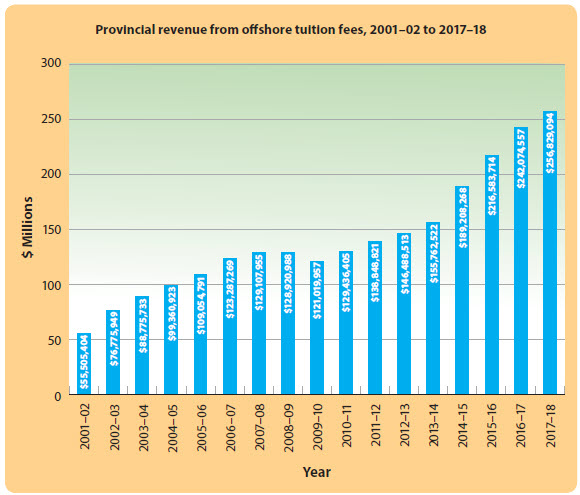

International students can be a positive addition to the public schools in providing broader experiences to domestic students. However, the significant increase in international students is primarily motivated economically, not educationally. The BC Liberal government encouraged districts to seek international students to gain revenue in the introduction of business practices to education. The impact has created inequality in access to extra resources among school districts.

In 2017-18, the total tuition collected by school districts was $257 million, but most of that was raised in just a dozen districts. These districts have an advantage over other districts because international student tuition provides discretionary funds to offer additional services to students, as compared to those districts with no additional international student revenue.

The West Vancouver school district, with the highest socio-economic status in the province, received 13% in tuition revenue over the amount provided by provincial grants. Coquitlam, with the largest number of students and revenue, received 12% in revenue over grants. Another dozen districts receive 6% or more in additional revenue, while nearly half of districts receive zero or barely more.(For more detailed information, see https://bctf.ca/publications/ResearchReports.aspx?id=50830)

BC School District Revenue from International and Out-of-province Tuition 2

The Ministry of Education Funding Review Panel report released in December 2018, was titled "Improving Equity and Accountability." It did recognize that "not all school districts have the same ability to generate revenues which can lead to inequities in the levels of services being provided to students across the province." However, the Panel decided that no action should be taken to deal with the inequity. The Panel said "it does not make sense to penalize a select group of school districts for being entrepreneurial."

This demonstrates the degree to which market approaches and inevitable inequalities have been normalized.

3. Specialty Academies are inequitable

As part of the competition and "choice" agenda adopted by the BC Liberal government, an amendment was made to the School Act that provided for "specialty academies." These academies are to "reflect an emphasis on a particular sport, activity or subject area" and are to "meet learning outcomes that are in addition to the learning outcomes that a standard educational program must meet." (School Act Regulation 219/08)

One rationale for these academies is competition-both to attract students who might otherwise go to private schools, or to attract students into the district from another district, and the provincial funding grants they bring with them.

Many districts have created academies. The most common type appears to be for hockey, with other sports including baseball, softball, basketball, golf swimming, soccer, rugby, volleyball, lacrosse, snow sports, fencing, table tennis, kickboxing and equestrianism. Fewer programs are in other areas such as dance, digital arts, animation, Microsoft IT, robotics, and film.

Source: BC School Districts' Audited Financial Statements, Schedule 2A, International and Out-of-province Student Tuition Revenue

The School Act provides that "a board may charge a student enrolled in a specialty academy fees relating to the direct costs incurred by the board in providing the specialty academy." Those fees vary, with a general range from $2 1000 to $51200 per school year, with the most expensive being an elite hockey academy at $17,000. This leads to obvious questions about inequities in access. While small funds may be available for bursaries in some districts/ these are clearly programs that exclude most students who face barriers such as immigrant status, family income or access to transportation.

A second problem, as Tara Ehrcke states in the Times Colonist "is the impact these choices have on all the other students in the school system. When one group chooses to attend special schools or programs, it affects the diversity of both the choice group/ but also the remaining school population. The effect can be informal segregation/ typically along socio-economic lines." (February 28,2019 1 https://bit./y/2TkW7dJ)

Often private contractors are hired to offer the specific training for the academy. While they would have to undergo criminal record checks/ they do not necessarily have teacher certificates.

Teachers have reported that academies can create a sense of 2nd-class students when preferential treatment is given to those in academies. The scheduling requirements of the academies often take precedence over those of the rest of the courses and may use facilities not available for other students/ negatively affecting non-academy students and teachers.

4. Funding of independent schools has increased

BCTF policy has long been opposed to the funding of independent schools.

Independent schools receive funds based on a percentage of the per-pupil amount in the school district in which the school is located. Group 1 schools (most of the religion-based schools) receive 50% and the Group 2 schools whose per-student operating costs exceed the Ministry grants paid to local Boards of Education receive 35%.

Although the percentage for basic grants stays the same/ other changes have led to larger amounts going to independent schools. Independent schools are now given 100% as much as public schools for students with special needs in categories that receive funding based on identification.

Students in independent school Distributed Learning programs receive 63% as much as the provincial grant to districts per student for public school DL programs. Grants increase when there are enrolment increases and these have gone up substantially in the independent DL programs.

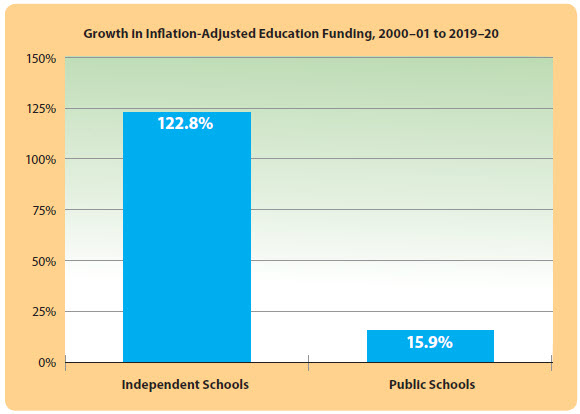

As a result of enrolment increases and progressively more generous funding policies,public expenditures on independent schools have grown at a faster rate than for public schools.3

The Ministry reports that the trend is projected to reverse in the 2019-20 provincial budget, with projected increases in public school funding being 3.7% and independent school funding being 2.4%.

Source: Ministry of Education. (Various Years). Service Plan. Victoria: Government of British Columbia.

Statistics Canada. (2019). Table 18-10-0005-01 Consumer Price Index, annual average, not seasonally adjusted.

5. Students with special needs are being isolated in independent DL school programs.

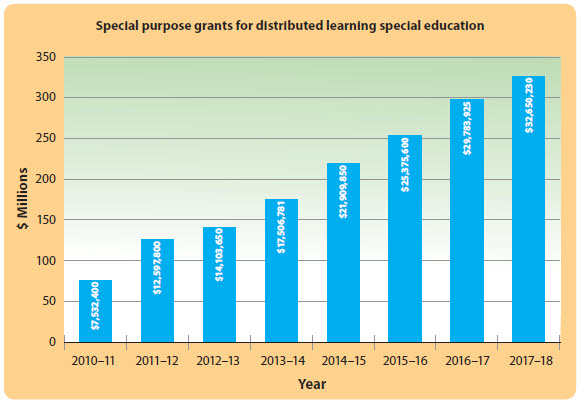

Enrolment has grown rapidly in the number of students who have 100% special needs funding and are in an independent school DL program 4

These students with special needs have become such a big part of the independent DL program that about 50% of all the provincial grants to independent DL programs are for students with special needs.

Why are large numbers of parents of students with special needs putting their children in independent school DL programs?

The key is the difference in how funding affects the services available.

Public school districts receive special needs funding generated by a designated student that is directed to programs that provide the support for all the students in the district. The independent school receives the same amount of special needs funding, but it is directed to services for the specific identified student. Most of the funds go to hiring an Education Assistant, and often the school will allow the parent to have a significant say in choosing the EA and directing their work.

Source: BC Ministry of Education. Ministry of Education - Independent Schools Enrolment and Funding Data

Parents make the choice because of the way the provincial funding gives them a feeling of more control over the resources devoted to their child, particularly in the context of insufficient funding and service in the public schools to meet the needs of all the students with special needs.

The result of these policies is that more funding flows to independent schools. Ironically, at a time when full inclusion is the policy direction of government its funding policies are encouraging parents to take their children out of schools with other children. In DL programs, most of these students with special needs are at home without other students and with an Education Assistant, and may see a teacher, at most infrequently.

Conclusion—privatization has been produced—and can be reversed—by government policy

Both finance and program decisions have encouraged privatization and marketization. Policy changes to improve equity and encourage public education options can reverse this. Some examples:

- Policies can focus on students in public schools who take DL courses within their own district,if available,encouraging the development of blended and other forms of DL that provide face to-face support from a teacher.

- Policies that encourage or provide more benefits for taking DL courses or programs in independent schools can be changed.

- The international student program can be focused on educational advantages rather than primarily revenue-generation, and a structure developed that supports equity around the province in educational and financial results.

- Funding can support specialty programs that are open to all students, not specialty academies as separate programs open only to those whose families can afford them.

- Funding for independent schools can be eliminated or reduced such as by reversing the pattern of increases (e.g., DL from 50% of 63%).

___________________________

- Source: BC Ministry of Education. (2019). BC Schools - Student Enrolment and FTE by Grade

- Source: BC School districts' Audited Financial Statements,Schedule 2A, International and Out-of-province student tuition revenue

- Source: Ministry of Education. (Various Years). Service Plan.Victoria: Government of British Columbia.

Statistics Canada. (2017). Table 326-0021 Consumer Price Index—annual (2002=100). Ottawa: CANSIM.

- Source: BC Ministry of Education